While this ruling clearly prohibited further segregation in public educational facilities, the Supreme Court did not dictate how these facilities should go about desegregating, which caused violent clashes in several states once integration was attempted. The court later issued a second ruling, Brown II, that ordered states to desegregate their schools “with all deliberate speed.”

Today, you can visit the sites affected by the ruling in Brown v. Board of Education and learn about the brave people who championed integration – sometimes even risking their lives. Taking in these sites on an extended road trip, or just visiting a few of them on a shorter jaunt, will allow you to see the scope of desegregation in the United States.

Topeka, Kansas

Kansas law allowed school districts to maintain racially segregated elementary schools for Black and white students in certain communities. The NAACP chapter in Topeka recruited 13 Black parents to attempt to enroll their children in the school closest to their homes, even if that school was designated for white children only. One of these parents was Oliver L. Brown, the named plaintiff in the case. His daughter Linda had to walk six blocks to catch a bus to her Black elementary school, Monroe Elementary, while a white elementary school, Sumner Elementary, was just seven blocks from the Browns’ home. When Linda and the other 19 children were refused enrollment based on their race, the 13 parents became the plaintiffs in the case that would come to be known as Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka.

Monroe Elementary, where Linda Brown attended, was designated a U.S. National Historic Site by the National Park Service in 1992. Visit the rehabilitated school and civil rights interpretive center on your visit to Topeka. Sumner Elementary is currently vacant, but plans are in place to turn it into a civil rights memorial and community center.

Little Rock, Arkansas

The next stop on your trip is Little Rock, Arkansas, home of the “Little Rock Nine.” After the ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, the Little Rock School Board agreed to comply with the decision and move forward with integrating its schools. Superintendent Virgil Blossom submitted a plan of gradual integration to be implemented in September of the 1957 school year. The NAACP registered nine Black students to attend Little Rock Central High School, a previously all-white facility. Selected for their outstanding grades and good attendance, the Little Rock Nine were Ernest Green, Elizabeth Eckford, Jefferson Thomas, Terrence Roberts, Carlotta Walls LaNier, Minnijean Brown, Gloria Ray Karlmark, Thelma Mothershed and Melba Pattillo Beals.

Despite the Supreme Court’s ruling and the superintendent’s plan for integration, several segregationist organizations threatened to physically block the Black students from entering Little Rock Central High. Arkansas Gov. Orval Faubus deployed the Arkansas National Guard to prevent the Little Rock Nine from entering the school on September 4, 1957. Photographs of the soldiers blocking their entry spread across the country, shining a national spotlight on Little Rock’s school board and the governor. President Dwight D. Eisenhower stepped in and sent federal troops to aid the integration process and protect the nine students upon their entry to the school. By the end of September, all nine students had been admitted to Little Rock Central High and were protected by the 101st Airborne Division.

During the school year, the Little Rock Nine endured verbal, emotional and physical abuse from white students. Melba Pattillo had acid thrown into her eyes, and Minnijean Brown was verbally confronted and abused. Although Gov. Faubus continued to fight against desegregation, the Little Rock Nine became symbols of hope in the struggle for integration. Ernest Green became the first African-American to graduate from Little Rock Central High.

You can trace the steps of the Little Rock Nine by visiting Little Rock Central High, a still-functioning school and a designated National Historic Site. The building also includes a civil rights museum in partnership with the National Park Service, so you dive even deeper into the story of the Little Rock Nine.

Next, drive past the Daisy Bates House, home of then-Arkansas NCAAP President Daisy Bates, which served as a command post for organizing the integration of Little Rock Central High School. It is not open to the public, but private tours are available by reservation.

Oxford, Mississippi

As late as 1961, the University of Mississippi in Oxford was still segregated and only admitting white students. James Meredith, a Black man, applied for admission to the University of Mississippi, believing it was within his civil rights to attend a public, state-funded university. The school rejected Meredith for admission twice, prompting Medgar Evers and the Mississippi chapter of the NAACP to support Meredith and help him file a lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Mississippi, alleging that he was denied admission because of his race. The United States Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit ruled that Meredith did have the right to be admitted to the university, and the United States Supreme Court upheld the appeals court ruling.

On September 13, 1962, when the District Court entered an injunction directing university officials to register Meredith, the segregationist state legislature quickly looked for loopholes to prevent his registration. It passed a law that declared no person could be admitted to the university who has been convicted of any felony offense or a “crime or moral turpitude.” On this same day, Meredith was convicted of false voter registration. The federal government fought back against these state legislature decrees, and on September 28, 1962, the Court of Appeals found Mississippi Gov. Ross Barnett in civil contempt and ordered that he be arrested and pay a fine of $10,000 each day that he kept refusing Meredith’s admission.

U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy had 500 U.S. marshals escort Meredith during his registration, and President Kennedy issued a proclamation ordering anyone obstructing the law to cease and desist.

Once the police presence was removed on the evening of September 29, a violent riot broke out on campus. President Kennedy sent the Mississippi National Guard and federal troops to the university to help gain control, but before the violence ended, two people had been fatally shot and many others were injured, including federal marshals who were hit with rocks, bricks and gunfire.

Despite the rioting, the next day, October 1, 1962, James Meredith officially became the first African-American student to enroll at the University of Mississippi. He was treated badly during his time at the university, enduring intense and continuous harassment and isolation, but he persevered. Meredith graduated from the University of Mississippi with a degree in political science on August 18, 1963.

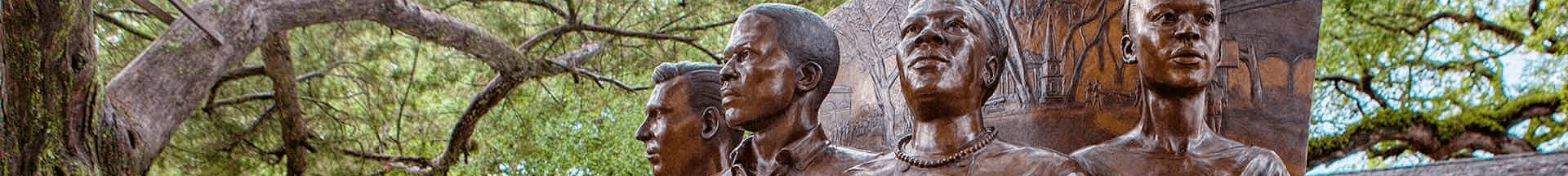

A historical marker designates the site of the rioting. When you visit today, you can see the Lyceum, part of the Circle Historic District at the University of Mississippi. The Lyceum is the only surviving building of the original five buildings that made up the early university. A statue of James Meredith also stands at the site.

New Orleans, Louisiana

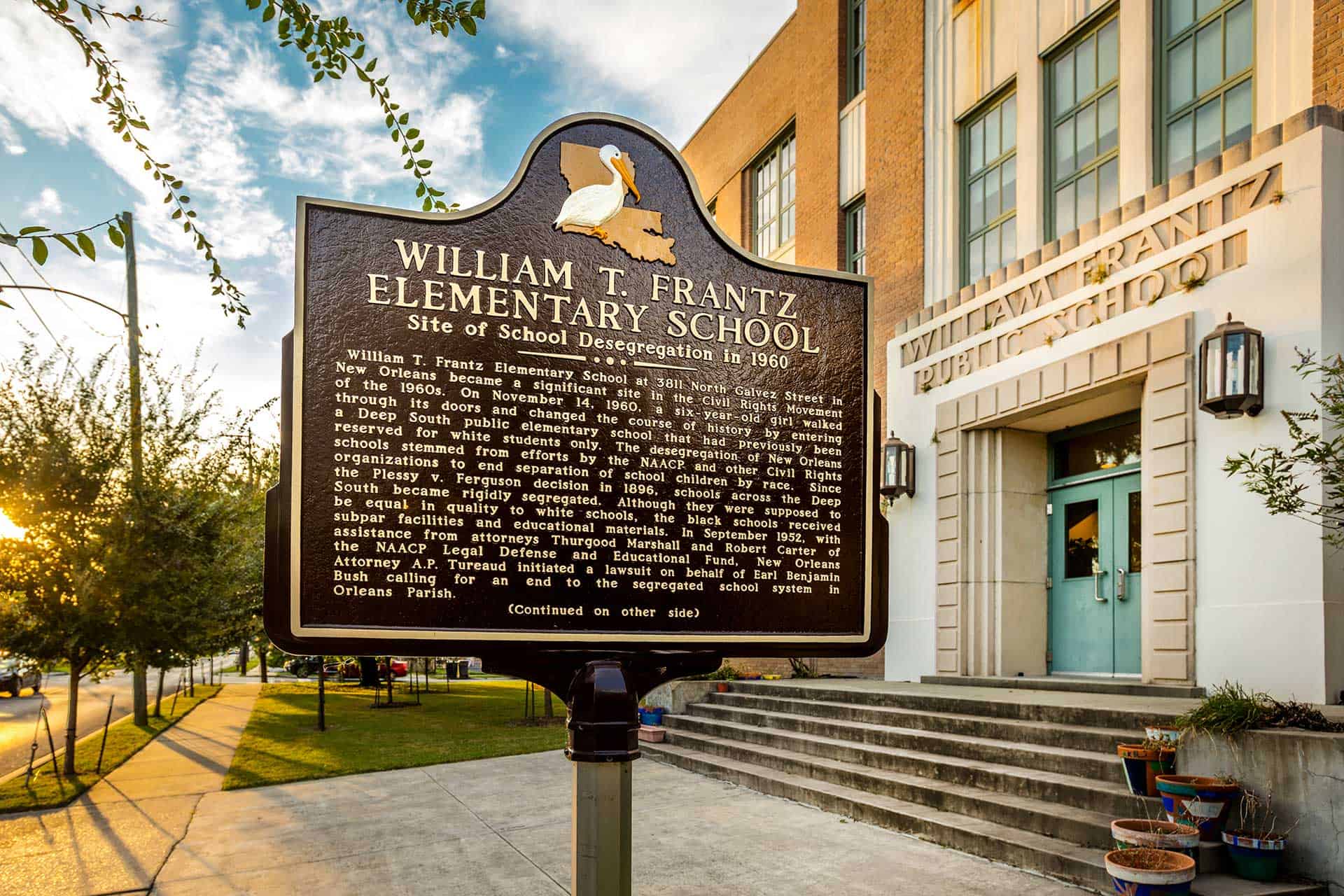

In 1960, 6-year-old Ruby Bridges and five other Black children passed a test that determined whether they could attend William Frantz Elementary, an all-white school in New Orleans. Ruby became the only one of the six to attend the school. During her first year there, federal marshals escorted Ruby to school for her protection. A photograph of her and four federal marshals has become iconic.

When Ruby reached the school on her first day, she was met by an angry crowd. White parents pulled their children out of the school, and teachers refused to do their jobs while a Black student was attending. The exception was Barbara Henry, who taught Bridges for an entire year. The girl was the only student in the classroom.

Ruby was threatened with poisoning on a daily basis, and a child psychiatrist met with her weekly. Her family also experienced harassment. Ruby’s father lost his job, and her grandparents were turned off the land where they were sharecroppers. However, there were members of the community who helped Ruby and her family. She has told stories of white families who kept bringing their children to the same school, even crossing through the protest to do so, and a neighbor who gave her father a job. Others acted as protectors by keeping an eye on Ruby’s house and walking behind the marshals’ car when they escorted Ruby to school.

The former William Frantz Elementary School is now home to Akili Academy, a charter school. Ruby’s legacy is preserved, however, with a statue in the courtyard. And room 2306 of the school has been restored to the way it would have looked when Ruby attended. To learn about tours of the facility, visit the contact page on the Akili Academy website.

While in New Orleans, schedule a tour of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit. This active federal government building was the site of several court decisions leading to desegregation by four judges famously known as the “Fifth Four” in the 1950s and 1960s. Overlooking Lafayette Square, the building is now a National Historic Landmark.

Tuscaloosa, Alabama

Foster Auditorium at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa is the site of the infamous “Stand in the Schoolhouse Door” incident. George C. Wallace, segregationist governor of Alabama, had promised during his campaign not to desegregate the University of Alabama, and on June 11, 1963, he stood in the doorway of Foster Auditorium to physically block two Black students, Vivian Malone and James Hood, from entering the building and enrolling in the school. President Kennedy intervened, calling in the Alabama National Guard to protect the students and allow them to enter. Gov. Wallace eventually left and returned to the state capital, and Malone and Hood were permitted to enter and register. This event marked a victory for integration, and Kennedy’s intercession sent a powerful message to segregationist officials across the country.

Foster Auditorium, now a National Historic Landmark, is still in use at the university, and a historical marker stands outside the building.

Berea, Kentucky

Berea College in Berea, Kentucky, was the first college established in the United States with the intention of educating Black and white students in a completely integrated setting. Established on these terms in 1855, the Kentucky legislature segregated the college in 1904 when it passed the Day Law, which mandated segregation. The college filed a lawsuit – Berea College v. Commonwealth of Kentucky – to fight this, but the Supreme Court determined that the state of Kentucky had the right to regulate Berea College because it was incorporated by the state.

The Day Law stayed in effect until 1950, when it was amended to allow Black students to enroll in Berea College only if they could not find similar courses at the Kentucky State College for Negroes. However, in 1954, the Brown v. Board of Education decision overturned Berea College v. Commonwealth of Kentucky, and the school was integrated once again.

Tensions surrounding integration remained high, and in the 1960s and 1970s, Berea’s Black students fought for more African-American representation on the faculty and administration. These students staged a 20-hour sit-in at the president’s office in Lincoln Hall to ensure that three Berea students who had been arrested for civil rights activities were treated fairly.

Lincoln Hall, still an active academic building, is now a National Historic Landmark. To visit, call the Berea College Visitor Center at 859-985-3197 to schedule a campus tour.

Farmville and Richmond, Virginia

Robert Russa Moton High School was built in 1939 in Farmville, Virginia, as an educational facility for Black students. Designed to hold 180 students, by the 1940s, 450 students were crammed into the building. The roof leaked so badly when it rained that students had to hold umbrellas to stay dry. The Prince Edward County all-white school board refused funding to expand Moton’s facilities, so long, temporary buildings covered with roofing material were constructed to handle the overflow of students.

In 1951, 16-year-old Barbara Johns and John Arthur Stokes led a group of students in a walkout protesting the school’s poor conditions. The NAACP joined forces with the students and reframed the goal of the fight as school integration rather than improving the conditions at the all-Black school. Attorneys Spottswood Robinson and Oliver Hill filed suit in 1951. Though the state rejected Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, it was later incorporated into Brown v. Board of Education.

Though the decision in Brown v. Board of Education mandated the integration of public school systems, integration in Prince Edward County was a long and contentious process. A statewide anti-integration campaign called “Massive Resistance” emerged, and the county school board refused to fund any public schools that planned to integrate. As a result, there were no public schools in the county between 1959 and 1964. The Prince Edward School Foundation established several private schools known as “segregation academies” because only white children were welcome. In 1964, Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County went before the United States Supreme Court, and the court ordered the reopening of the public schools in Prince Edward County with full integration.

The building that was formerly Moton High School served as a primary school facility until 1993. After it closed permanently, the school was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1998. Today, you can visit the Moton School, which has been turned into a museum commemorating the fight for civil rights in public education and features a permanent exhibit called “The Moton School Story: Children of Courage.” The museum also contains Moton High School memorabilia, other relics of the Civil Rights Movement, and oral histories of teachers and students who were part of the walkout. Stop by for a docent-guided tour of the museum and learn more about the brave students who led the fight for integration in Farmville.

You can also visit the Virginia state capital of Richmond to see a beautiful bronze and marble sculpture of Barbara Johns, the courageous 16-year-old girl at the front lines of the walkout.

While you’re in Virginia, there’s also potential for a bonus trip to visit some of the 41 sites of the Civil Rights in Education Heritage Trail. Moton School is an anchor site, so you can start there and experience several other places that were at the center of the struggle for integration.

Washington, D.C.

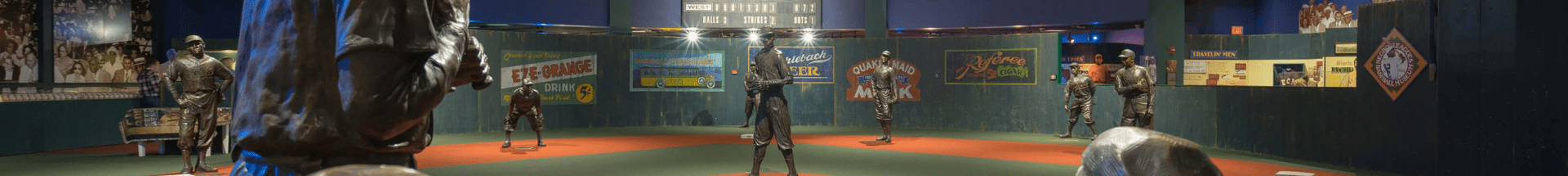

Washington, D.C., is home to the United States Supreme Court building, where the Warren Court (named for Chief Justice Earl Warren who presided at the time) handed down its milestone decision in Brown v. Board of Education. Howard University provided preparation of Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP’s legal strategy that resulted in the historic decision. Nine of the 10 attorneys who argued in the Brown case were professors or graduates of Howard University School of Law. A local school, John Philip Sousa Junior High School, was the subject of one of the five cases argued in Brown.

The school is a National Historic Landmark but is not open to the public. However, you can enjoy a self-guided walking tour of historic Howard University. The Supreme Court building offers videos, exhibitions and docent-led lectures, as well as the opportunity to visit the courtroom itself on a first-come, first-served basis. Please check the Supreme Court’s website for rules regarding visits.

Wilmington, Delaware

One of the five lawsuits combined in the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case was based in Wilmington, Delaware. Gebhart v. Belton was filed in 1951 when parents of students who were being bused to the all-Black Howard High School sued to allow their children admittance to Claymont High School, which was all-white at the time. Of the five cases in Brown v. Board of Education, the Howard High School case was the only one that resulted in an order of integration at the state level.

The school was declared a National Historic Landmark in 2005, and it was completely renovated in 2014 to become Howard High School of Technology. The school is not open for public tours.