Greensboro, North Carolina

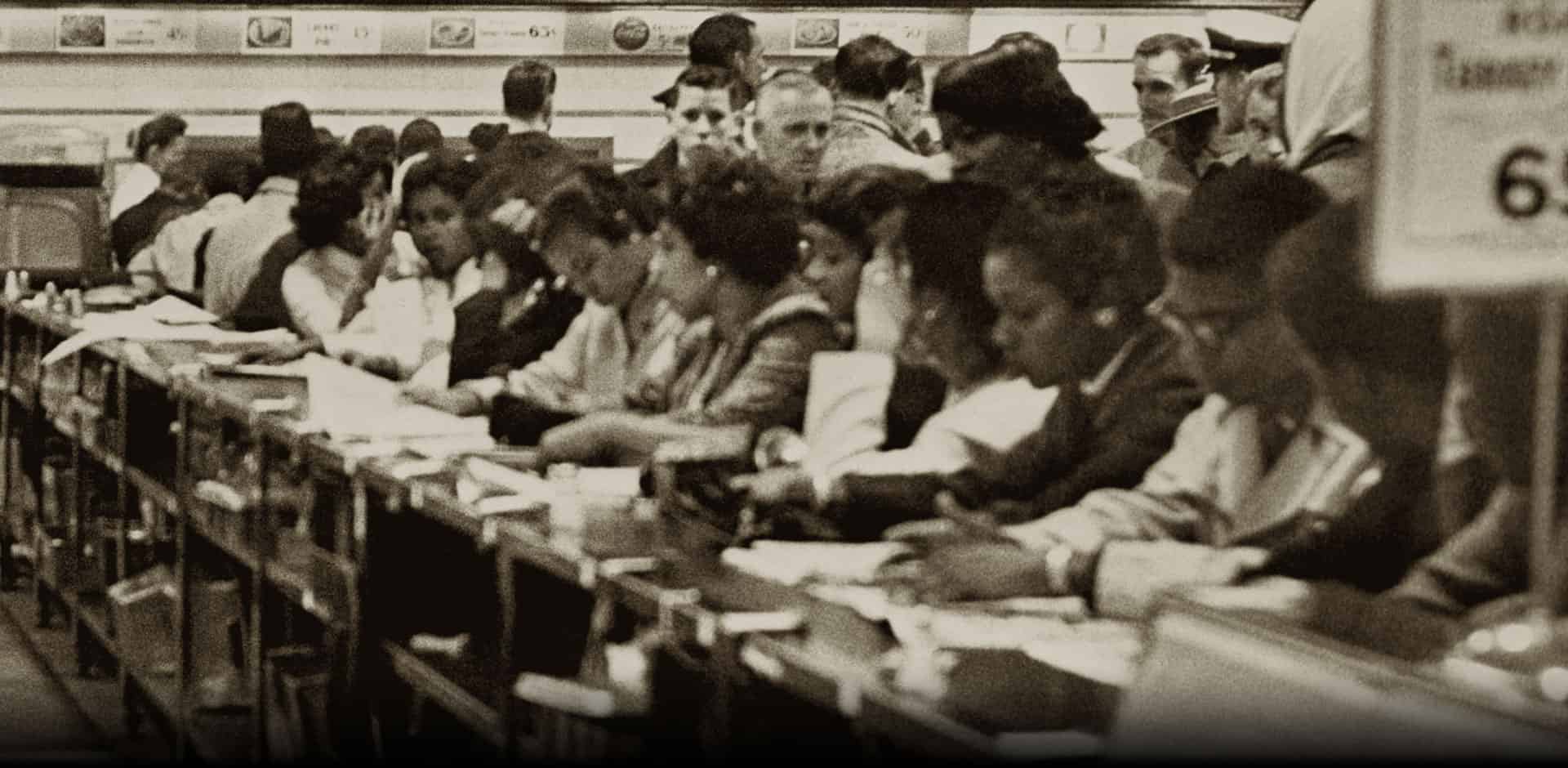

The sit-in at the lunch counter of Woolworth’s department store in Greensboro on February 1, 1960, was the impetus for the larger sit-in movement that spread across the country. Four Black students from Agricultural & Technical College of North Carolina (now North Carolina A&T State University) – Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair Jr. and David Richmond – sat down at the lunch counter inside the store and were refused service when they each asked for a cup of coffee. Even though they were not served, the four men stayed at the counter until the store closed that night.

The next day, the sit-in grew to include more than 20 participants, including women from neighboring Bennett College. The students were harassed and heckled by white patrons, but they remained at the counter and did not fight back. The following day, more than 60 people joined the sit-in, and local newspapers and news stations came to Woolworth’s to report on the event. On February 4, more than 300 students participated in the sit-in, which expanded to the lunch counter at Kress, a nearby store.

Students in other North Carolina cities, including Winston-Salem, Durham, Raleigh and Charlotte, also organized their own sit-ins at segregated businesses, and the movement spread to other states, such as Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia and Mississippi. In locations where sit-ins were taking place, segregated businesses were losing money. Woolworth’s in Greensboro lost a reported $200,000 due to boycotts, and on July 25, 1960, store manager Charles Harris decided to desegregate the store. He requested that four of his Black employees change out of their uniforms and order at the counter. That day, the four employees became the first Black customers to be served at any Woolworth’s lunch counter.

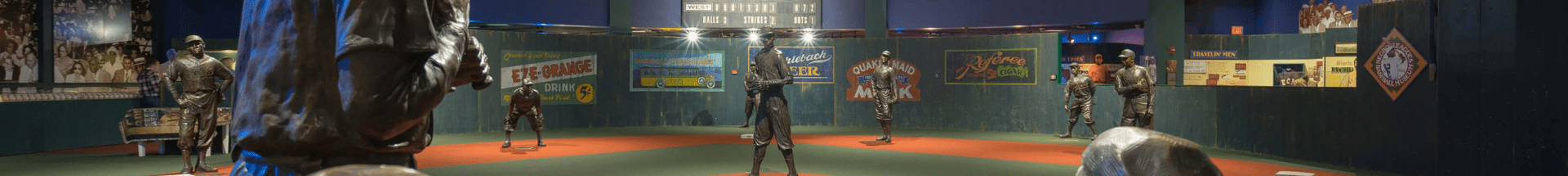

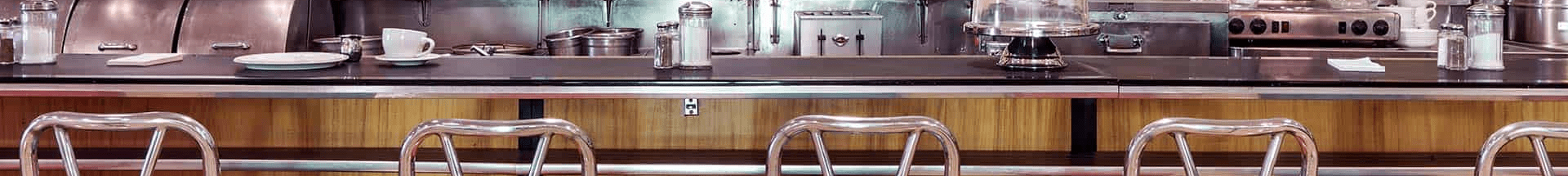

The seats and counter remain in the original building in Greensboro, which is now part of the International Civil Rights Center & Museum.

Orangeburg, South Carolina

Sit-ins were also taking root in South Carolina in 1960. Students organized a sit-in at the segregated lunch counter of S.H. Kress & Co. in Orangeburg’s business district. This action sparked multiple boycotts of segregated businesses in the town. A group of 1,000 students gathered to protest segregation in Orangeburg businesses, and when they refused to disperse upon the police chief’s order, police officers and firemen attacked them with fire hoses and tear gas. Protestors continued to act peacefully, but they were pinned against walls and pushed to the ground.

For breaching the peace, 388 students were arrested and 341 were eventually convicted and fined $50 each, though none of them ended up paying this fine because all appealed. Their defense lawyer, NAACP attorney Matthew Perry, was briefly jailed for his defense of the students. South Carolina State University President Benner C. Turner threatened expulsion from the school for any students who continued demonstrating against segregation, but sit-ins continued at Kress.

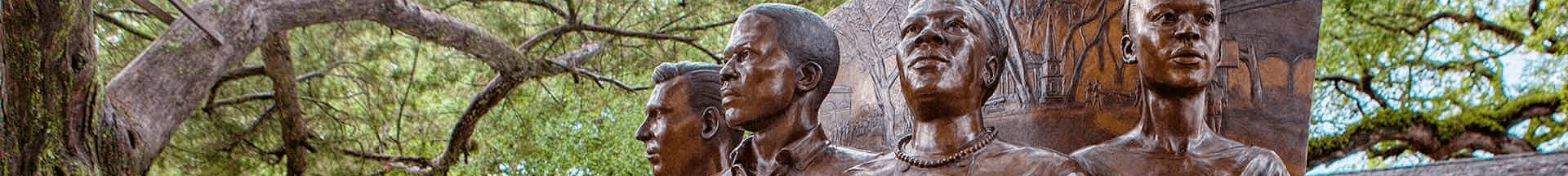

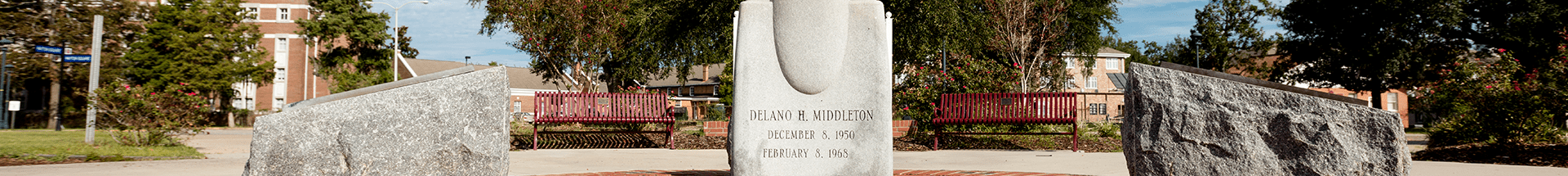

Racial tensions remained high throughout the 1960s, and in 1968, the hostility boiled over into violence after several incidents at All Star Bowling Lanes, whose owner refused to desegregate. When 200 students gathered on the South Carolina State University campus to protest unequal treatment at the bowling alley, the South Carolina Highway Patrol fired into the crowd of demonstrators, killing three students and injuring 27 people.

Today, you can visit the South Carolina State College Historic District and the site of Orangeburg Massacre. There are active academic buildings from the Civil Rights Movement period, as well as statues memorializing the three Black students who lost their lives in the massacre. Though All Star Bowling Lanes is vacant, National Park Service rangers offer tours of the interior of the building at specified times.

Rock Hill, South Carolina

On January 31, 1961, nine students from Friendship Junior College in Rock Hill walked into McCrory’s five-and-dime store, sat at the lunch counter and ordered food and drinks. They were refused service and instructed to leave, but they did not get up. All nine students were arrested.

Following the arrests, 10 people were convicted of breaching the peace and trespassing and given a choice between spending 30 days in jail or paying a $100 fine. All but one chose jail time, which started the “jail, not bail” approach that spread to demonstrations in other cities. Through the next several months, sit-ins and marches continued in Rock Hill.

In 2015, Judge John C. Hayes III overturned the convictions of the nine men who were punished for the McCrory’s sit-in, saying, “We cannot rewrite history, but we can right history.”

The McCrory’s building still houses an active restaurant, and the original counter where the sit-in occurred is engraved with the names of the Friendship Nine. You can visit the building free of charge, and you can even grab breakfast, lunch or dinner at the famous site.

Charleston, South Carolina

On April 1, 1960, students from Burke High School congregated at the S.H. Kress & Co. lunch counter to stage a sit-in. Twenty-four students arrived around 11 a.m. They were refused service, but they remained seated and continued to behave respectfully, sometimes humming songs and praying together. Just before 5 p.m., the store closed, and police arrested the protestors. NAACP Branch President J. Arthur Brown paid the students’ bail, which was set at $10 each. The one-day sit-in was not as eventful as some of the other longer-term sit-ins around the country, but these students changed the tide in Charleston and opened the door for residents to acknowledge the poor treatment of African-Americans in their city.

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

The activism that began in Greensboro, North Carolina, spread to Louisiana. Seven students from Southern University in Baton Rouge staged a sit-in at the Kress lunch counter there on March 28, 1960. All seven were arrested for breaching the peace, and their bail was set at $1,500 each. The Rev. T.J. Jemison, a civil rights leader in Baton Rouge, raised the money for their bail, and the students returned to school.

On March 29, seven more students were arrested for a sit-in at the Sitman’s Drug Store lunch counter. Two were arrested for a sit-in at the Greyhound Bus Station. On March 30, angry students walked out of their classes at Southern University and marched to the Louisiana State Capitol in protest. Southern University President Felton Clark suspended all 16 arrested students for an indefinite period. Despite some classroom boycotts the following day, the sit-in campaign eventually lost steam, with 15 of the 16 arrested students asking for re-admittance to the school.

The U.S. Supreme Court overturned all 16 convictions in 1960, and Baton Rouge lunch counters were desegregated in 1963. Tours of both the Louisiana State Capitol Building and the campus of Southern University are available.