The Fight for Voting Rights in Selma

In protest of laws that kept Black citizens from participating in politics by limiting their right to vote, the Dallas County Voters League fought to register Black voters in the 1950s and 1960s. They were met with resistance from state and local officials, as well as the Ku Klux Klan and the White Citizens’ Council.

On Oct. 7, 1963, James Forman and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) helped organize more than 300 Black citizens from Dallas County to go to the voter registration office in Selma. Though they waited in line all day, only a few were allowed to fill out applications, all of which were denied by white officials. The FBI and lawyers with the United States Department of Justice were present during this event – known as “Freedom Day” – but Selma officials were not punished for denying Black citizens their voter registrations.

SNCC Chairman (now Georgia Congressman) John Lewis led 50 Black citizens to the courthouse on July 6, 1964, another voter registration day. All 50 were arrested by the county sheriff and denied voter applications. Three days later, Judge James Hare issued an injunction that made it illegal for two or more people to gather in sponsorship of civil rights or voting rights in Selma.

On Jan. 2, 1965, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke at Brown Chapel AME Church, leading local activists to redouble their efforts to fight for voting rights. Protests and voter registration drives began again in Selma. On Feb. 1, the arrest of Dr. King helped bring national attention to Selma. On the same day, protests and sit-ins in support of the Selma voting rights campaign persisted in cities around the country. On Feb. 4, President Lyndon B. Johnson publicly declared his support for the campaign.

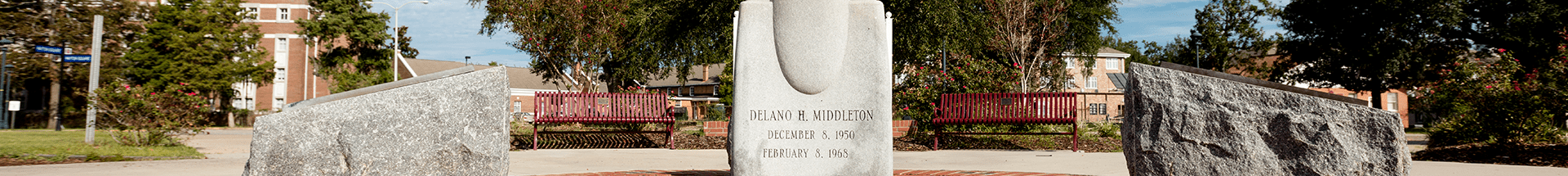

Dr. King, congressmen and members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference met regularly in Selma at the home of Richie Jean Jackson to strategize in their efforts to help Blacks exercise their right to vote. On Feb. 18, Jimmie Lee Jackson, a local activist, was beaten by police officers and shot by an Alabama state trooper, leading to his death eight days later. Jackson’s murder motivated more local action, and the Selma to Montgomery marches were planned.

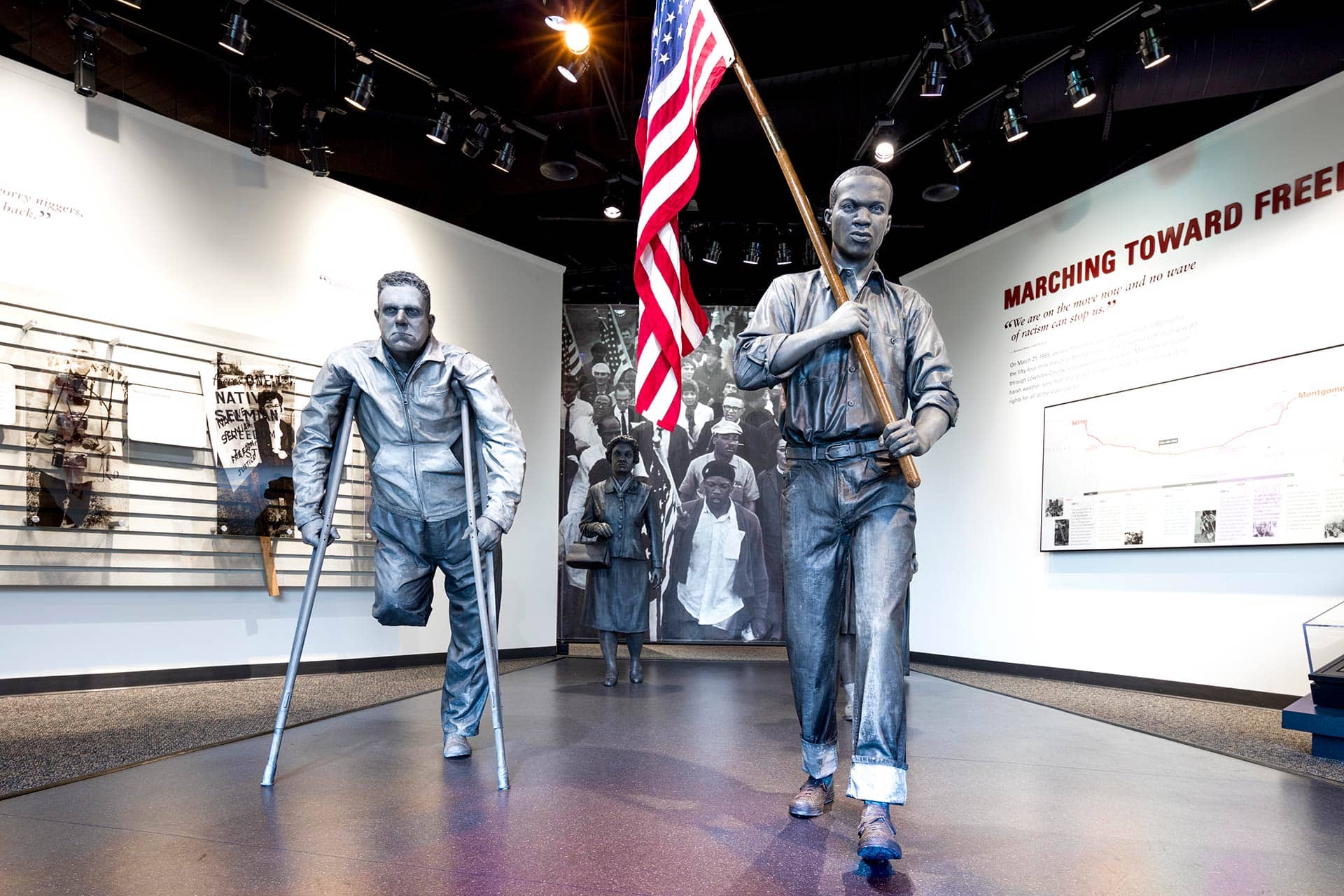

The First March – Bloody Sunday

The first of three protest marches took place on March 7, 1965, a day known as Bloody Sunday. Led by John Lewis and the Rev. Hosea Williams, as many as 600 civil rights protesters began marching from Selma to Montgomery along U.S. Highway 80. As marchers crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, they were met by state troopers and armed citizens. Troopers on horseback charged the marchers, attacking them with nightsticks and tear gas. The crowd also participated in the attack, leaving many marchers severely injured and some even beaten unconscious. Fifty marchers were injured and 17 were hospitalized. The brutal attack was televised across the nation, and public outrage at the violence helped the Selma voting rights campaign gain support.

Bloody Sunday also motivated Federal Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr. to overrule a law segregationists were using in their attempt to stop the Selma-to-Montgomery march. Johnson’s action effectively granted protesters the right to march and gave the wider public a closer look at the events in Selma.

The Second March

A second march, deemed “Turnaround Tuesday,” took place on March 9, 1965, with support from people across the country. Dr. King led 2,500 marchers to the Edmund Pettus Bridge and turned around without crossing into the unincorporated area of the county.

Three Unitarian Universalist ministers who had traveled to Selma to participate in the march were beaten by four Ku Klux Klan members that night. The Rev. James Reeb died from his injuries in the hospital on March 11, sparking more public outcry across America.

Because the second march could not have guaranteed safe passage out of the county, students from the Tuskegee Institute joined the effort and formed a separate march to the Alabama State Capitol in Montgomery.

On March 15, 1965, President Johnson, encouraged by the events in Selma, demanded that Congress pass voting rights legislation. The joint session of Congress was nationally televised live. President Johnson said Selma was “a turning point in man’s unending search for freedom,” and the Voting Rights Bill was formally introduced on March 17.

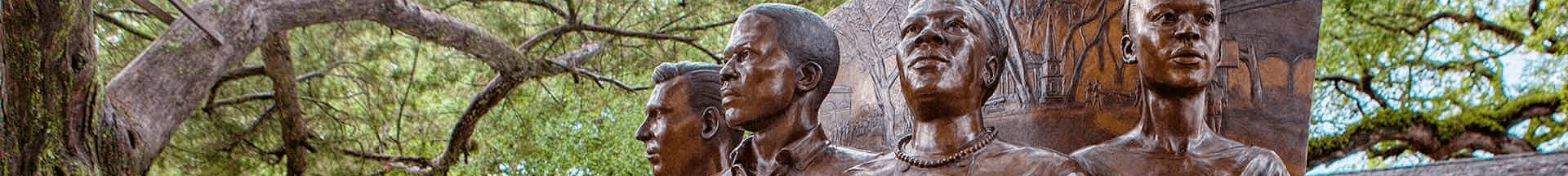

The Third March

On March 21, 1965, the third march began, with Dr. King and 8,000 marchers of all races leaving from Brown Chapel AME Church and heading to Montgomery. The marchers arrived in Montgomery County on March 24, and by March 25, 25,000 people marched to the steps of the Alabama State Capitol Building, where Dr. King delivered his famous speech, “How Long, Not Long.”

By March 1966, over 11,000 Blacks had successfully registered to vote in Selma, and five Black citizens ran for office in Dallas County. Also in that year, the National Park Service designated the 54-mile path from Selma to Montgomery a National Historic Trail.

On Feb. 24, 2016, surviving march leaders U.S. Rep. John Lewis and the Rev. Frederick Reese accepted a Congressional Gold Medal on behalf of the Selma marchers.