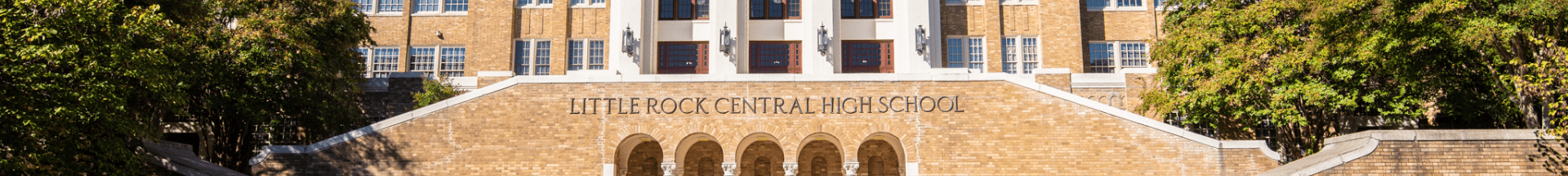

Little Rock, Arkansas

Central High School

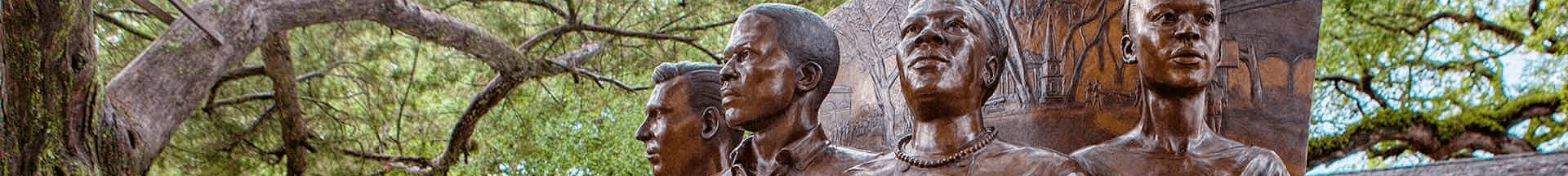

Things were supposed to be changing for the better. The federal government made desegregation a law, but in the fall of 1957, when nine African American students courageously tried to make their way through the front doors of the all-white Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, things turned ugly. Governor Orval Faubus called in the National Guard to block the Little Rock Nine’s way, and chaos ensued, with thousands of white protesters angrily pushing back against their integration efforts.

Later on September 25, President Dwight Eisenhower called in federal troops for backup to enforce the law. The Little Rock Nine were escorted to class and became symbols of bravery in the integration struggle during the civil rights movement.

Today, students of all colors attend Central High. And in addition to being home to the historic public high school, the campus also contains a visitors center run by the National Park Service. Group leaders can arrange tours to look at this critical piece of civil rights education history. Though they aren’t allowed inside the school, groups can explore the visitors center and museum and see nearby Magnolia Mobil Gas Station — once the heart of Little Rock’s live media reporting during the civil rights movement. “It’s a very visual experience [and] very hands-on for all kinds of learners — auditory and visual,” said Brian Schweiger, chief of interpretation at Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site.

Schweiger encourages visitors to take a walk around the site, mainly through the Commemorative Gardens, where there’s a photo exhibition of Central High’s history. For an immersive audio experience, he recommends visitors download the National Park Service app or enhance the tour with a podcast-style history of the school done in partnership with current students there.

NPS.GOV/CHSC

TOPEKA, KANSAS

BROWN V. BOARD OF EDUCATION NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE

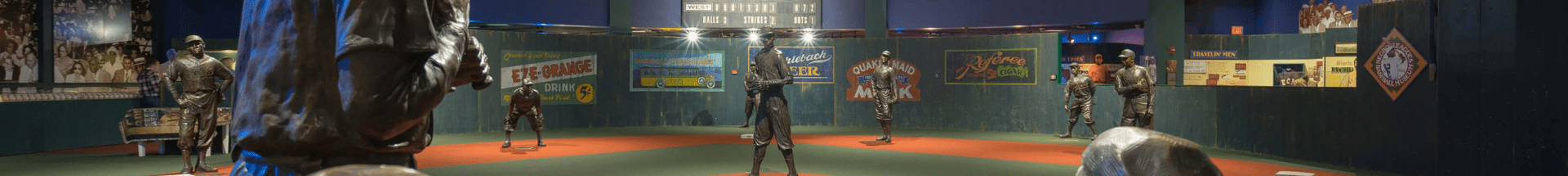

Long considered one of the most critical turning points in U.S. education history and the civil rights movement, the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in the Brown v. Board of Education was a landmark victory. Today, Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site in Topeka, Kansas, preserves the site of one of the schools involved in the case and is worth planning a trip around.

Visitors will learn about the five individual lawsuits, all with the same goal of ending segregation, that were combined by the Supreme Court to challenge the fallacy of separate but equal public schools.

It was a time of deep inequality in the school system, and students and their families refused to stop fighting until the landmark Supreme Court case outlawed segregation nationally, changing the educational landscape forever.

For visitors looking to immerse themselves in the inner workings of the case, the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site has extensive exhibitions, including a film that explores racism and segregation history. There’s a photo gallery documenting the years leading up to the Supreme Court decision and a legacy room that speaks to the impact and importance of Brown v. Board of Education.

“Prepare for an impactful experience,” said Nicholas Murray, park ranger of interpretation, education, and visitor services at the site. “Our exhibits are designed to be emotionally impactful. Right away, when you walk into the building, we have segregated signs up to get you in the mindset of what it was like to live in a segregated society.” The fight for the right for integrated, equal education was a long and arduous one. Visit this important site to learn something new yourself.

NPS.GOV/BRVB

RUSSELLVILLE, KENTUCKY

SEEK MUSEUM

One of Russellville, Kentucky’s most notable figures of the civil rights movement was Alice Allison Dunnigan, a native of Logan County who fiercely fought in the struggle for equal rights. From the very beginning, Dunnigan, a teacher in Kentucky’s segregated schools, fought for improved facilities and resources, going so far as to create learning materials that included the Black history often left out of textbooks.

“She went to segregated schools in Kentucky, a segregated college, which became Kentucky State, and then came back to teach in segregated schools,” said Joseph Clark of the SEEK Museum. “So throughout her life, education was a big part of the stories she wrote and the issues she addressed.”

Dunnigan went on to become the first Black woman to attend White House, Congress and Supreme Court press briefings. And she never took a back seat in those rooms but instead asked poignant questions to raise the public’s consciousness about segregation and Black voting rights.

Dunnigan’s legacy is celebrated at the SEEK Museum’s Payne-Dunnigan House. While walking through the home where she lived for decades, visitors can immerse themselves in the history of her work and the impact of other Kentuckians who fought for civil rights.

SEEKMUSEUM.ORG

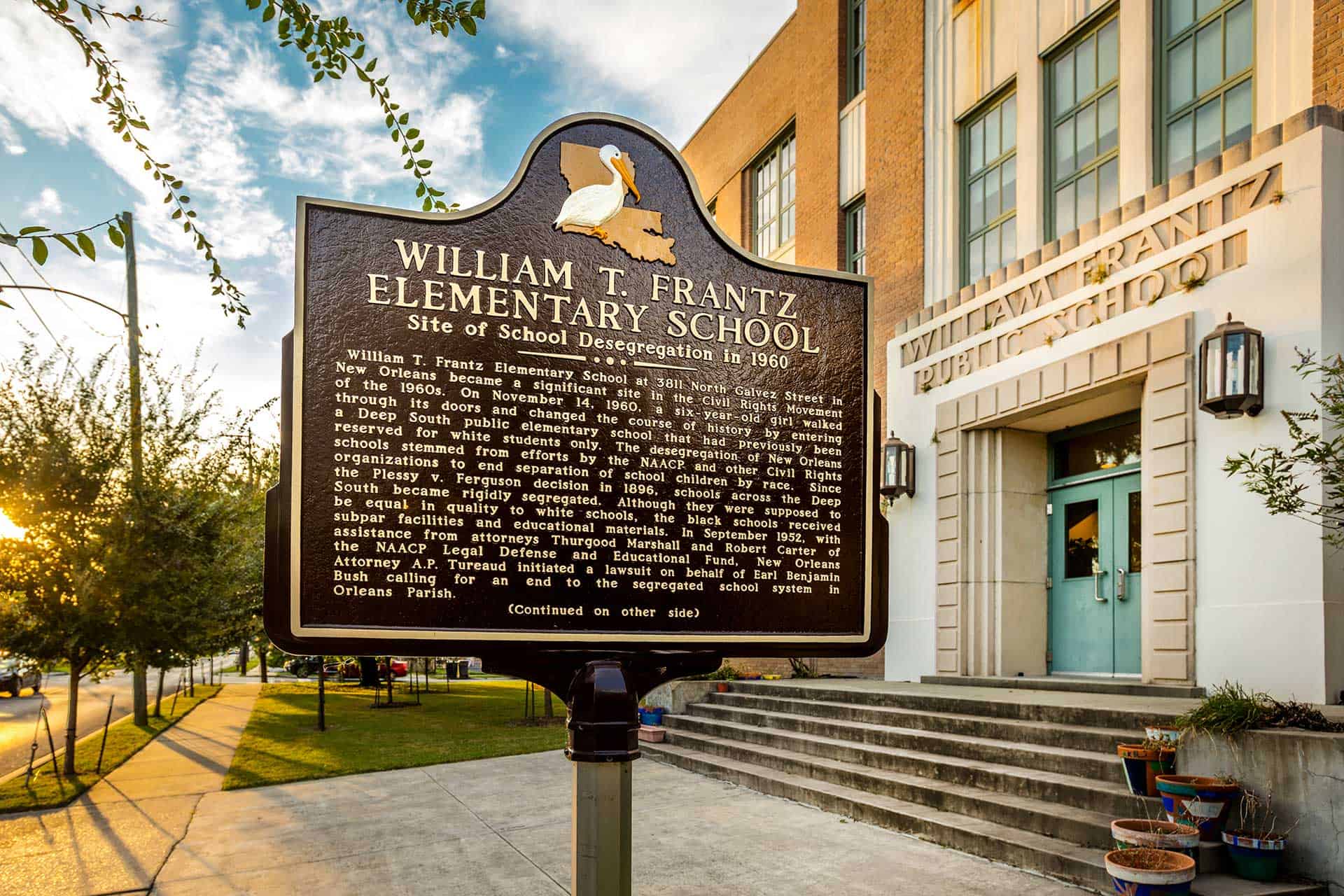

NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA

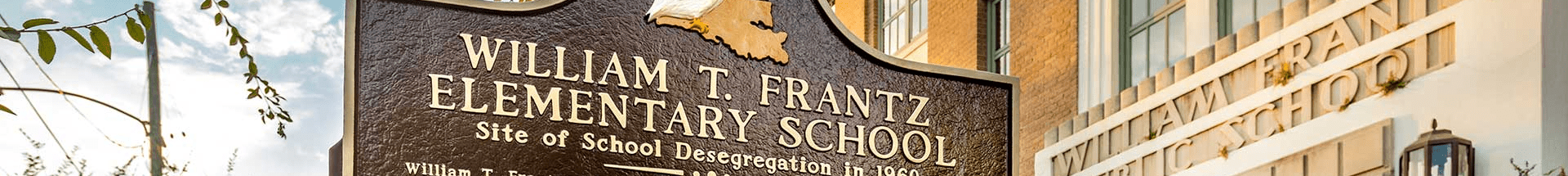

MCDONOUGH 19 & WILLIAM FRANTZ ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

New Orleans’ Lower 9th Ward was once home to McDonough 19 Elementary School, the fiery site of the 1960s integration struggle when three first-graders, Leona Tate, Gail Etienne and Tessie Prevost, helped desegregate their school. Although this was years after the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, many Southern schools had resisted the change. As with most other school integration struggles during the Civil Rights Movement, racists fiercely opposed it. When Tate, Etienne and Prevost first attempted to enter the school, they were heckled and spit on by white protestors. Federal troops were called in as violence grew too intense for the 6-year-olds. On their first day, the girls spent most of their time in the principal’s office before being escorted and confined to a single classroom for the entirety of the school year.

But the story of the McDonogh Three doesn’t end there. After the school building sat vacant for years, Leona Tate’s foundation raised enough money to purchase the facility. Today, the TEP Center is a cornerstone of the Lower 9th Ward community. The mixed-use building provides senior affordable housing, spaces for community groups and a living museum documenting the visual and oral histories of those who lived in the community during the civil rights era through post- Hurricane Katrina.

Tremaine Knighten-Riley, program director, said The TEP Center recently completed a $16.2 million renovation of historic McDonough 19.

“When folks come, they are initially immersed into the feeling of what Leona, Gail and Tessie experienced,” Knighten-Riley said. Visitors walk up the 18 steps and into the principal’s office exhibit before retracing the student’s efforts from the morning of the integration attempt to their isolating classroom experience on a guided tour that transports visitors back to that time.

A few minutes around the corner was William Frantz Elementary school, where another 6-year-old, Ruby Bridges, integrated into her school as its first Black student. Today, the building is used as a charter school, Akili Academy. Bridges’ legacy is preserved with a courtyard statue and a classroom restored to its original design, available for touring. Visitors wanting to experience the facility should contact the school directly to book a private tour.

TEPCENTER.ORG, AKILIACADEMY.ORG

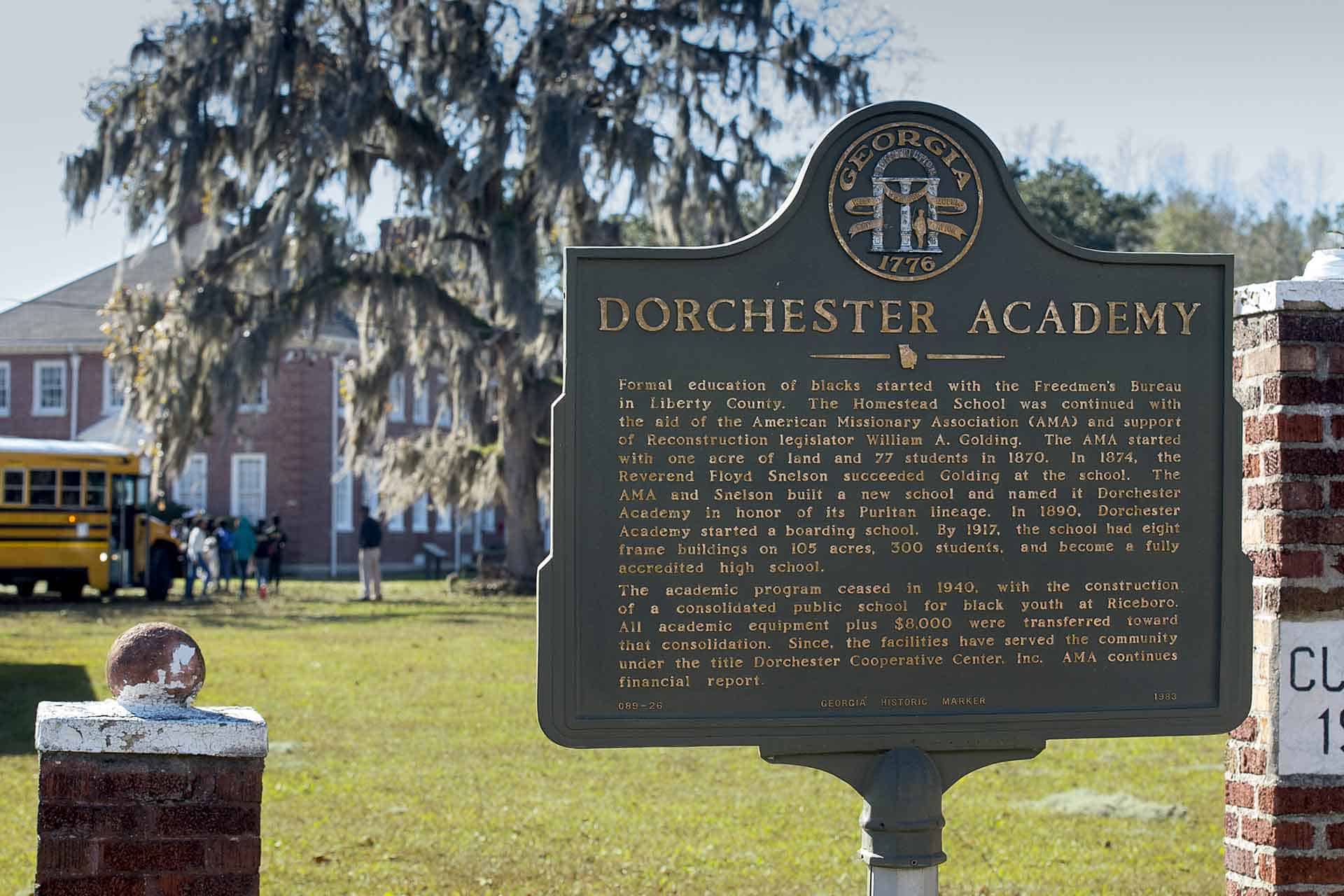

MIDWAY, GEORGIA

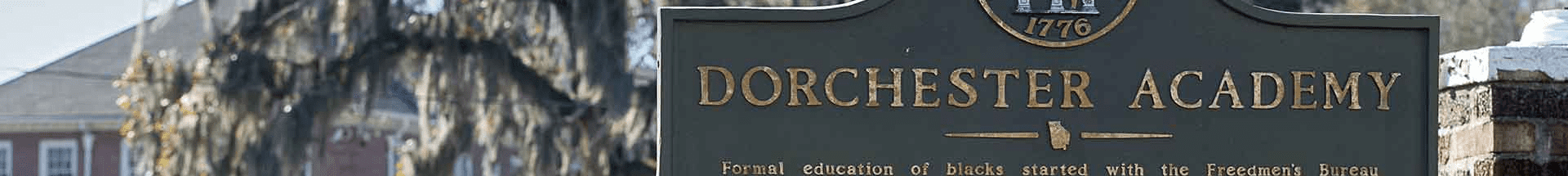

DORCHESTER ACADEMY

Located on the Georgia coast, Midway’s Dorchester Academy was a pillar of Black education during the civil rights movement. Now a museum, it began as a one-room schoolhouse and eventually became a key meeting place for 1960s civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Ralph Abernathy. Leaders strategized, planned and trained freely at the academy, which also served an integral part in educating Black adults. It’s here that educator Septima Clark helped busloads of adults learn how to read, write and do the math needed to help them pass anti-Black voter registration quizzes. Dorchester also became a safe haven for activists to let their hair down and rest from their tireless work.

The 30-acre campus was a remarkable place for all kinds of education, with students being trained in trades like blacksmithing and carpentry upon graduation. And the school graduated the first class of 12th-graders in the state’s history. But it was a challenging road. Many of Dorchester’s students walked dozens of miles each way to attend school.

Today the academy is a history museum, community center and an up and-coming community educational and research center. Travelers can join weekly guided tours of the grounds or plan a trip around events like the annual Walk to Dorchester, which takes place every Juneteenth in honor of the students who walked and worked hard for their education at a time when it didn’t come so easy.

DORCHESTERACADEMYIA.COM

To discover more about this travel guide, visit https://grouptravelleader.com/civilrights/