Arkansas Civil Rights Trail

The Arkansas Civil Rights Trail begins in Little Rock, which was the site of one of the major turning points of the civil rights movement. Groups that want to learn more about the state’s place in history should start at the Visitor’s Center at the Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site; the school was the first in the state to try to desegregate after the landmark Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education made it illegal to segregate public schools. Park rangers lead tours of the site daily, telling the stories of the nine Black students and the hardship and violence they endured as they tried to attend the all-white school.

LittleRock.com has a map that groups can use for a self-guided tour of civil rights sites, including the Testament: Little Rock Nine Memorial, which stands in front of the Arkansas State Capitol, and the Daisy Gatson Bates House Museum. Bates was president of the Arkansas chapter of the NAACP.

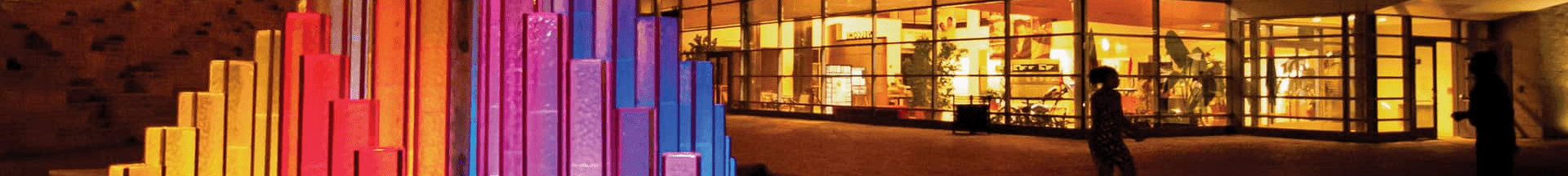

The William J. Clinton Presidential Center and Park is another spot on the trail; the center features exhibits about Clinton’s presidency and focuses on expanding civil rights to people around the world. The Historic Arkansas Museum has a permanent memorial — Giving Voice — to the 138 enslaved men, women and children who lived where the museum now stands, and exhibit feature topics such as African American history and local Black artists. The Mosaic Templars Cultural Center is the first publicly funded museum of African American history and culture in the state.

ARKANSAS.COM

Georgia’s Albany-to-Atlanta Black Heritage Tour

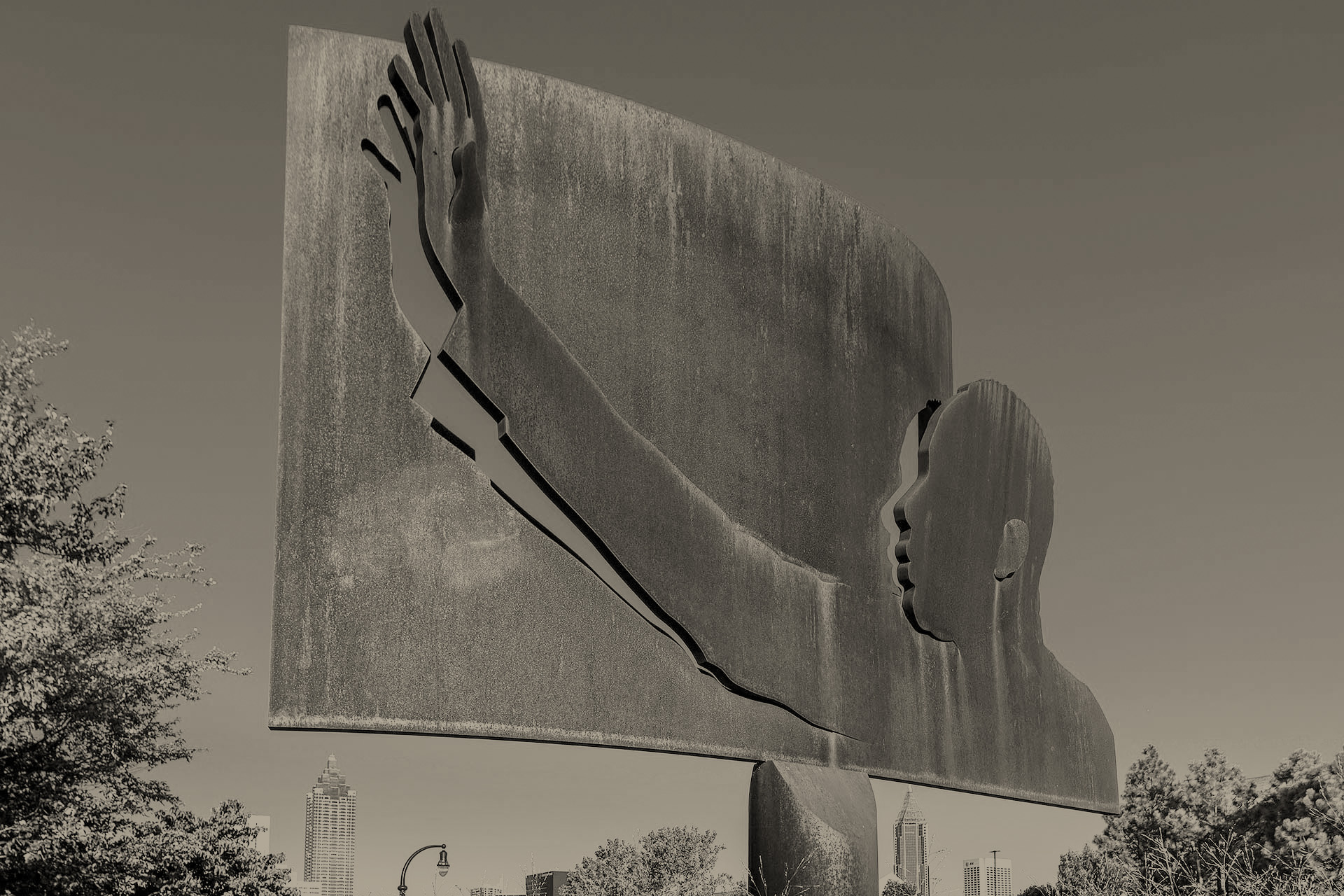

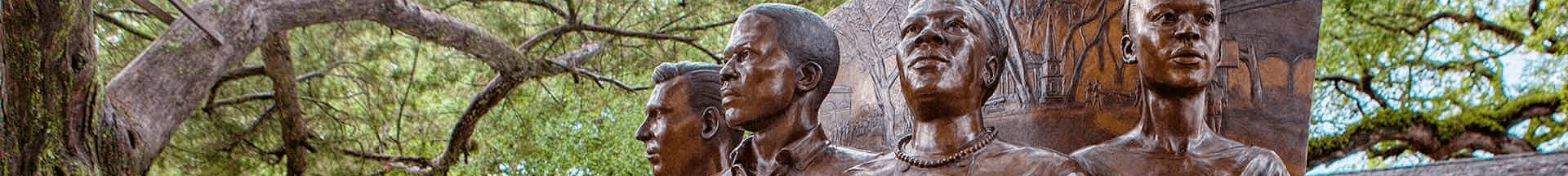

There are 11 must-see civil rights destinations in Georgia, many of them tied to the life of Martin Luther King Jr. They include historic churches in Albany that led a grassroots campaign to end discrimination in southwest Georgia, sites tied to King in Atlanta, and a historic school and meeting place for civil rights leaders in Midway, on Georgia’s coast.

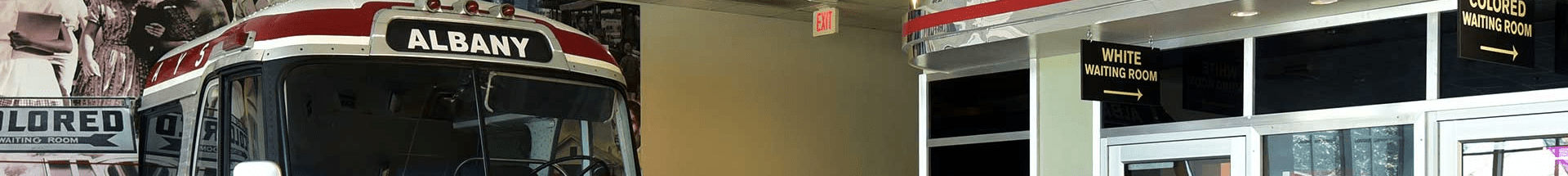

The Albany Civil Rights Museum and Institute is in the restored 1906 Old Mount Zion Church. It uses oral histories, photographs, documents, artifacts and exhibits to detail the civil rights struggle from voter registration and nonviolent protest to song, economic boycott and legal action. Across the street, the Shiloh Missionary Baptist Church was where mass meetings were held during the Albany civil rights movement. King spoke to members of both churches in 1961.

In Atlanta, groups begin their tour at the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park Visitor Center, where they can reserve tickets to tour his boyhood home. At the King Center, they can see the crypts where King and his wife are entombed. Freedom Hall features exhibits about the life and works of the Kings. The Ebenezer Baptist Church, where King’s father was pastor and King later became co-pastor, is another must-see. The National Center for Civil and Human Rights ties the events of the civil rights movement to today’s global human rights movements, and the Elbert P. Tuttle U.S. Court of Appeals Building was the location of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals during the civil rights movement. It is a National Historic Landmark because the court enforced the Brown v. Board of Education decision.

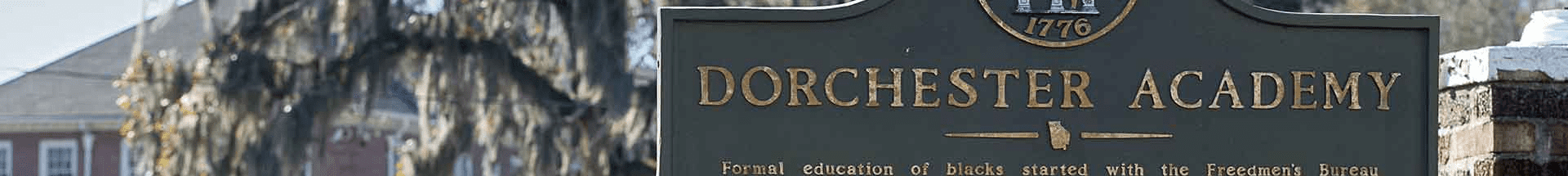

In Midway, the Dorchester Academy Boys’ Dormitory was one of two sites where the Southern Christian Leadership Conference held its citizenship education workshops during the 1960s.

EXPLOREGEORGIA.ORG

Kentucky Civil Rights Trail

There are four sites in Kentucky on the U.S. Civil Rights Trail. In Russellville, a park and the Seek Museum commemorate Alice Allison Dunnigan, the first African American woman to be admitted to the White House, Congressional and Supreme Court press corps; Dunnigan wrote for the Associated Negro Press. Russellville also has a restored Rosenwald school — these schools were built to educate poor, rural Black youth — as well as a jail where African Americans were taken to be lynched.

Berea College in Berea was the first interracial and coeducational college in the South until the Kentucky General Assembly passed the Day Law in 1904 prohibiting Black and white students from being educated together. Once that happened, the people at Berea College helped support the founding of the Lincoln Institute in Simpsonville to educate those displaced Black students. When African American students were allowed back 50 years later, they demonstrated to get African American teachers and staged several sit-ins at Lincoln Hall.

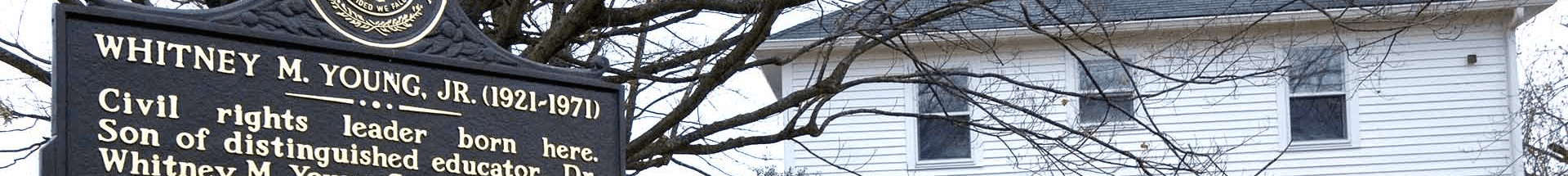

The Whitney Young Birthplace and Museum in Simpsonville tells the story of Whitney Young Jr., whose father was an educator and the head of the Lincoln Institute. Young became the head of the National Urban League, which, along with the NAACP, was at the forefront of the civil rights movement. His focus was on employment and jobs for African Americans.

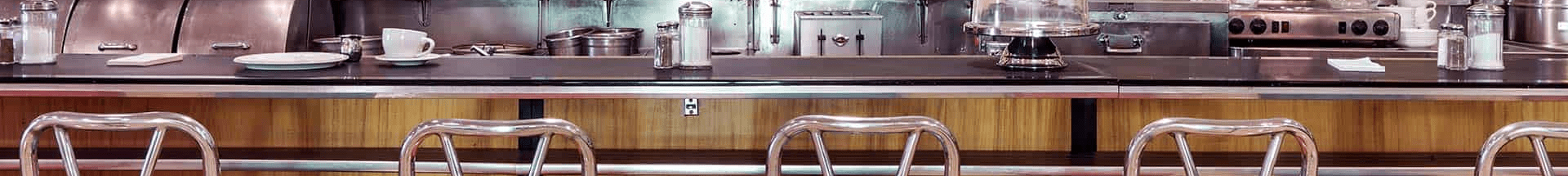

In Louisville, the Muhammad Ali Museum documents the boxer’s career and involvement with civil rights and as a humanitarian. The Louisville Downtown Civil Rights Trail features 11 markers that designate buildings that are no longer there: businesses like the old Woolworth’s, where Black people were not allowed to eat at the lunch counter, and stores where there were sit-ins or protests because Black people weren’t allowed to use the changing rooms. All in all, there is a lot of important history to see in Kentucky, plan your itinerary and discover it for yourself.

KENTUCKYTOURISM.COM

Missouri Civil Rights Trail

Groups that want to learn more about the civil rights movement in Missouri should start their journey on the steps of St. Louis’ Old Courthouse, which was the originating site of several groundbreaking Supreme Court cases regarding civil rights. A statue of Dred and Harriet Scott sits on the south lawn of the courthouse, facing the Gateway Arch and the Mississippi River, The Old Courthouse is part of the National Park Service’s Underground Railroad Network to Freedom.

The Field House Museum is a National Historic Landmark that once belonged to Roswell Field, the attorney who represented Dred Scott during his Supreme Court case.

The Griot Museum of Black History has exhibits on the adversity slaves endured in Missouri. Travelers can drive by the Shelley House, a private residence that was the center of the Shelley v. Kraemer Supreme Court case in 1948. A Black couple purchased the home, but the neighborhood had a covenant that prohibited minorities from living in the area. A neighbor, Louis Kraemer, sued the Shelleys to prevent them from moving in, but the court sided with the Shelleys, ending racial discrimination in housing.

The Mary Meachum Freedom Crossing is north of downtown and the site where Mary Meachum was caught helping slaves cross the Mississippi River to freedom. She and her husband, the Rev. John Berry Meachum, were part of the Underground Railroad.

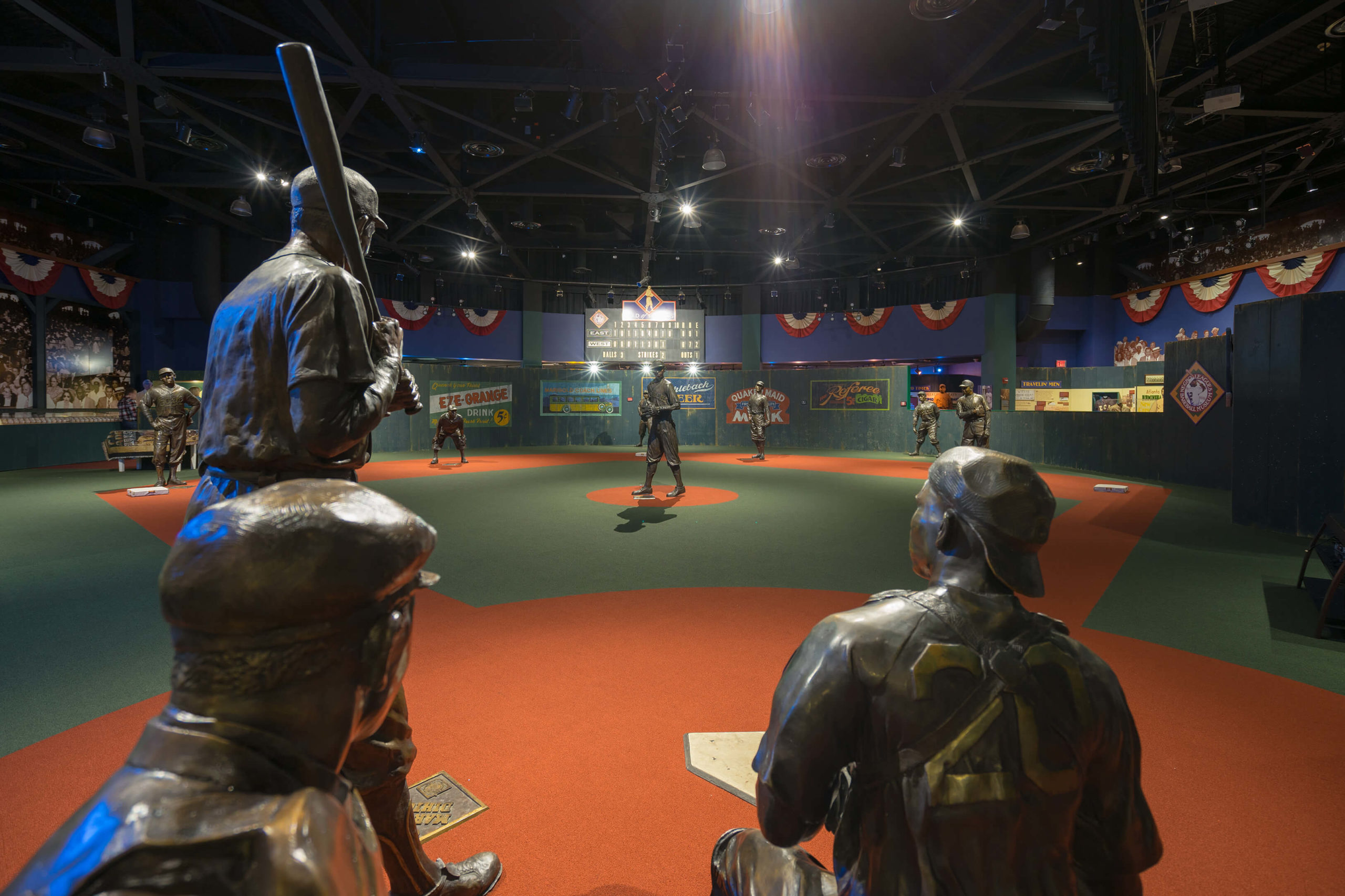

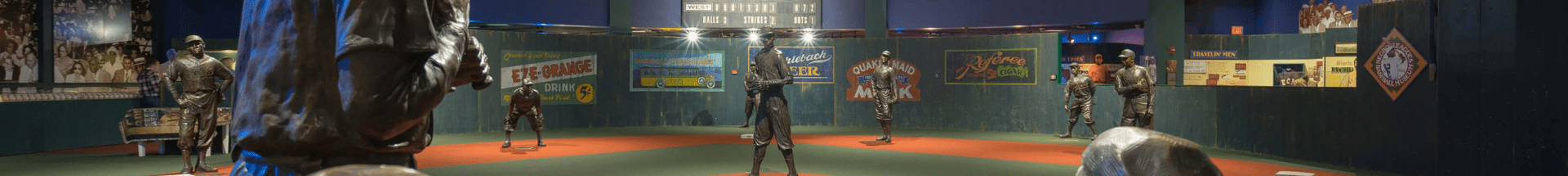

Lincoln University in Jefferson City was a college founded by former enslaved soldiers following the Civil War, and the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum in Independence features an exhibit dedicated to civil rights. Visitors learn about Harry Truman’s efforts toward equality in the U.S., including an executive order desegregating the federal workforce and military. The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City celebrates the rich history of African American baseball and its impact on the social advancement of America. Plan a trip and discover all the civil rights history Missouri has to offer.

VISITMO.COM

West Virginia Black History Tour

Harpers Ferry National Historical Park is a great first stop for any group that wants to learn more about Black history in West Virginia. Harpers Ferry was the site of a raid by abolitionist John Brown, who tried to spark a slave revolt in 1859. Visitors to the 3,647-acre historical park can tour John Brown’s Fort, the 1848 armory where Brown and his 18 raiders made their stand against federal forces, or tour 24 restored 19th-century buildings.

Another important site in the park is the Heyward Shepherd Monument, which commemorates a free Black man and innocent bystander who was the first person killed by Brown and his raiders. The all-Black choir at Storer College was asked to perform at the monument dedication ceremony in 1931. Pearl Tatten, the choir director, vehemently opposed performing at the dedication because African Americans supported what Brown was trying to do, but the white college president felt it would show goodwill if they did. Tatten used the opportunity to tell the crowd that her father wore the Blue during the Civil War and that African Americans were not looking back to the days of the Black mammy but forward to the rise of Black youth.

W.E.B. Du Bois heard about what Tatten did and came to Harpers Ferry with a tablet that laid out demands of which rights all people should have. He placed the tablet on a chair next to John Brown’s Fort and gave a rousing speech about it. The tablet is still there today.

In Charleston, groups can visit the home of Elizabeth Harden Gilmore, who pioneered efforts to integrate her state’s schools, housing and public accommodations and fought to pass legislation enforcing integration. In Huntington, visit the home of Memphis Tennessee Garrison, a teacher that helped organize a new NAACP branch in the region and served as national vice president of the NAACP Board of Directors in the mid-’60s. Explore the rich history in West Virginia and take your own journey through its fight for civil rights.

CIVILRIGHTSTRAIL.COM

To discover more about this travel guide, visit https://grouptravelleader.com/civilrights/